The manuscript finalised by this author around 1615 was published for the first time in 1936 after it had been found by a German scholar in the National Library of Copenhagen at the beginning of the 20th century. Meanwhile this library has produced a website, together with Rolena Adorno, an eminent scholar who has widely published on the life and work of Guaman Poma. The site includes the digitised photographs of the whole book (more than 1,000 pages) as well as a transcription with comments and a comprehensive bibliography. (Guaman Poma de Ayala [ca. 1615] Adorno & Boserup 2001.)

The richly illustrated chronicle, the Primer nueva coronica y buen gobierno, the First New Chronicle and Good Government describes both Peruvian Incaic history and the colonial present. Guaman Poma’s work comprises his version of Andean history and provides a comprehensive and complex image of colonial society. Part of the latter is the ‘good government’, a book of recommendations how social and political life should be organised so as to improve the indigenous population’s living conditions. The author (Guaman Poma de Ayala [ca. 1615] Adorno & Boserup 2001, p. 1, 5) directed his work to the King, but also thought that it would be beneficial to everyone living in or concerned with the Andes.

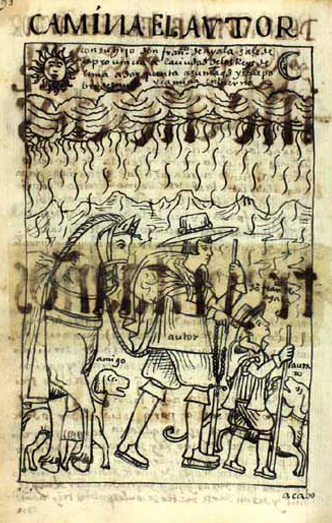

The author walking along … (Guaman Poma de Ayala [ca. 1615] Adorno & Boserup 2001, p. 1105); from the manuscript in the Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Although it is clear that Guaman Poma had a personal agenda (portraying himself as descendant of Inca and provincial nobility, and expressing his resentment for injustices suffered), his detailed description of Peruvian society reflects many other sources which largely confirm his criticism. The Andean author is ethnographer, writer, illustrator; he is a historian of the Western world and the Andes.

Portraying himself as a good Christian he criticises indigenous ‘misbeliefs’, but also Spanish misbehaviour. He is a documentarist of the colonial world, using explicit language to criticise bad customs and elaborate illustrations to present the reader with a visual impression. Although most of his work is written in Spanish (his own Andean version of it), there are numerous words, passages and even texts in indigenous languages, most of them in Quechua, the language of the Incas and Guaman Poma’s mother tongue. Moreover, besides concrete and explicit diction and illustrations, he uses textual imagery and metaphor as well as parody and satire.

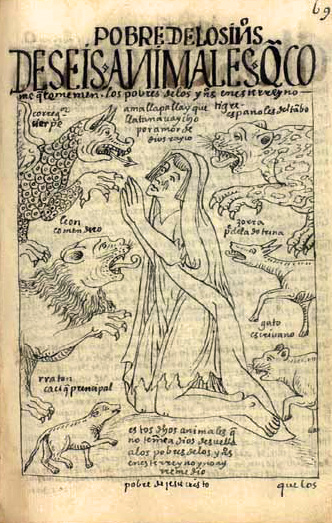

A combination of these linguistic resources, i.e. expressive and stylistic means, is found in his critique of colonial functionaries and the Christian prayers he composes. He goes beyond the literal usage of words, giving them complex and ambiguous figurative meanings. Through linguistic means, i.e. textual imagery, and visual image, Guaman Poma relates the Spanish colonialists to barbarians and thereby reverses their own concept of alterity which sees the indigenous peoples as uncivilised and the Europeans as civilised. In order to do so, the author uses textual and visual images of animals as metaphors for those authorities that, through injustice and abuse of their power, threaten the indigenous people’s personal lives and their social organisation.

In order to create this potentially multiple reading, in his imagery Guaman Poma draws on both European and Andean motifs and meanings. As in so much of his work, the imagery can be seen as an intentional fusion of Old and New World concepts, based on the general knowledge of his time. These images are contextualised, on the one hand, in an Andean heritage he wishes to highlight, and they are, on the other, framed by European concepts as an effort to make the Spanish reader understand what he wants to convey.

Both traditions were consciously employed by him to appeal to a Spanish and an Andean audience. Although he lived most of his life under the colonial regime and therefore in a world that had undergone some radical changes, the fact that he writes extensively about the past shows that he and his contemporaries were still familiar with or at least aware of Andean traditions (which, however, had of course started to become interrelated with European ones). (See Dedenbach-Salazar Sáenz In prep. 2013 Symbolic language in Guaman Poma.)

Of the poor Indians: the six animals which eat them and which they fear (Guaman Poma de Ayala [ca. 1615] Adorno & Boserup 2001, p. 708); from the manuscript of the Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark

In his comprehensive image of colonial society, much space is given to the clergy. He mostly depicts the parish priests – partly due to his own personal experience – as avaricious and evil. This is expressed very clearly in Quechua sermons he assigns to the priests and, which, instead of talking about Christian life, have the preacher’s exploitation and threats of the indigenous listener as their theme. They also show the priests’ insufficient Quechua proficiency. In this way the author as meta-narrator embeds ‘quoted’ speech in his text and, without further comment, almost like a journalist, accuses the parish priests satirically.

|

Guaman Poma |

English translation (SDS) |

|

machasca roncosca hundasca borrachosca guausasca putillasconas suaconas laycaconas hicheseroconas p[adr]emana ofrecinq[ui]corita colquita – |

Drunkards, hoarse ones, plastered ones, pissed ones, corrupt ones, indecent ones, thieves, evil witches, witches, you the Father not offer gold and money. |

|

guarmicona p[adr]e supay diablo ynfierno cinata manchanqui |

Women, you fear the Father like supay, the Devil, Hell. |

|

mana uacita ricuyta monanquicho |

You do not want to see my house. |

|

rreymanta apo yngamanta asuam apom cani |

I am more powerful than the King than the Lord Inca. |

|

coracam cani lesenciadom cani |

I am curaca (indigenous leader). I am licenciado (academic). |

|

uarcoscayquichicme |

I will hang you. |

|

mana sapatollaymanpas merecinquicho |

You deserve not even mine shoes. |

|

cayllata alli oyarillauay |

Only this, please listen well to me. |

|

dios uacaychasunquichic churillaycona |

God protects you, my dear children. |

|

ancha uaylloscay cuyascay captiqui yachachique cay sermonnipe |

Because you are so tenderly loved by me, I teach you in this my sermon. |

|

noca yayayq[ui] p[adr]e niq[ui] |

I, your Father, tell you. |

Guaman Poma: Sermon ascribed to Loayza (Guaman Poma de Ayala [ca. 1615] Adorno & Boserup 2001, p. 626, transl. SDS)

Guaman Poma, as author of the whole work, describes the priests; these, in turn, in the texts assigned to them, depict the indigenous population in a negative light and at the same time show themselves as exploiters – in this embedding framework Guaman Poma constructs a double alterity. (See Dedenbach-Salazar Sáenz Ms. 1993 Guaman Poma; 2004 El lenguaje como parodia.)

Sermon of the parish priest (Guaman Poma de Ayala [ca. 1615] Adorno & Boserup 2001, p. 623); from the manuscript in the Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark.