The confession manuals written in Spanish and Amerindian languages (such as Aztec or Quechua), were designed to help the priests to obtain insight into the cultural behaviour of their parishioners and, of course, to lead them to behave properly in European terms. Like in Europe, they normally followed the ten commandments, but from very early on they included questions which took into special account the indigenous people’s own culture, or at least what the priests believed this to be.

In the European confessionary written by Francisco de Victoria in 1562 (Victoria 1562 Confessionario), it was to be asked, with respect to the first commandment, among other questions, about infidelity, idolatry (if the Devil or something else but the true God was worshipped), blasphemy, false or superfluous cults, and the invocation of the Devil or demons. This latter as well as asking for divination practices reflect what was apparently still common practice in Spanish society (and is documented also through other kinds of sources).

In the southern Peruvian Spanish-Quechua-Aymara confessionary edited by the Third Provincial Council of Lima (Confessionario para los curas de indios 1585) this was much more specific, documenting that only 50 years after the conquest the Christian priests had gained some insight into Andean beliefs: Have you worshipped huacas, villcas [Andean deities], mountains, rivers, the sun? Have you made offerings of clothing, coca leaves, guinea pigs to them? Have you confessed yourself with a witch? Have you made any offerings to the dead? The first three and the last question mentioned here are practices which are still alive today in the Andes.

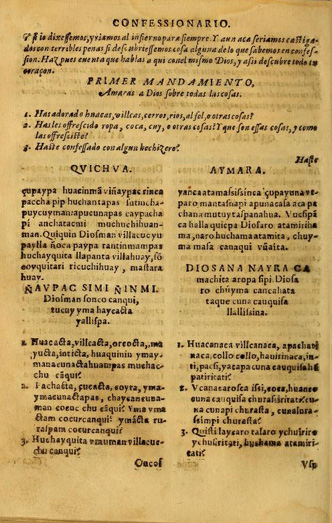

Confessionary about the first commandment: “Have you adored huacas, villcas …?”, (Confessionario para los curas de indios 1585, fol. 6v ); from the copy of the John Carter Brown Library, Providence, Rhode Island, USA

The sixth commandment which was to assure that only those sexual customs sanctioned by the Church were practised, specified several unallowed manners of behaviour in Victoria’s confessionary: adultery, incest, sacrilege against the vote of chastity, intercourse with a virgin or unmarried woman, homosexuality, masturbation, ‘unnatural’ positions in intercourse, and touching a woman indecently.

In the Quechua confessionary edited by the Third Lima Council, details were asked which reflect some of the behaviour listed by Victoria, such as whether the ‘sinner’ was living with a partner outside marriage. Moreover, exact information was to be asked for, for example: “Have you sinned with other unmarried or married women? How many times with each married one? How many times with each unmarried one?” Other questions ask if the sinner had forced a woman to have intercourse, or whether he made a woman drunk in order to sin with her. It is interesting that questions had to be asked not only to discover direct incest, but also ‘social’ incest: “Have you sinned with two sisters? With mother and daughter? With a relative of your wife? What kin relationship did she have with your wife?” Whilst these questions remind us of the Spanish context of confraternities, others aim at finding out whether the sinner had had intercourse in a church or a cemetery, whether a kind of herb was used for amorous spells (huacanqui) or a witch was consulted in order to get close to a woman, and finally whether he had intercourse with animals (as there is no general word for ‘animal’ in Quechua, this is translated as ‘llama’).

It seems to me that, apart form the standard questions, the other ones I have mentioned here, might have been similar in rural Spain, revealing the theologians’ preconceptions about folk culture rather than about pagan culture – or implicitly admitting that both were thought to be related.

Another field of interest for the modern reader is that of potential unlawful behaviour of the indigenous ruling and administrative elite; the 1583 confessionary includes 24 questions for the ethnic chief, some for indigenous mayors and also a few for ‘witches’ (the latter would evidently only have been asked in case a person was suspected to be a witch). Thus it is asked about the use of indigenous labour by the ethnic chief: “Who works and sows your fields? The Indians through corvée labour? And does this form of taking turns come from Inca times or is it by order of the inspectors or governors, or do you force them to do it? Are the fields you have inherited from your parents, or have you taken them from the Indians, or were they from deceased ones who died without heirs, or did they belong to the community, and you have taken them for yourself?” The priests also had to ask about the chiefs’ involvement with native religious practices: “Have you protected witches and idolators, and unmarried couples, and have you received some remuneration for this?”

This kind of information, should it have been provided by the sinner, would have made the priest an extremely well informed and thereby powerful person in the community.

For the researcher in colonial studies these confessionaries are a rich source of material. They shed light on how the Spanish rulers gained more and more insight into the functioning of indigenous society. They also show how those societies changed during less than a hundred years. On the other hand, we may want to ask whether at least some of these questions project the Europeans’ own (mis-)behaviour – for example in the question whether the sinner hit an Indian because he was annoyed with him – onto the others as much as they give evidence of the existence of it. Moreover, we may want to ask whether some of the close examination of the sexual behaviour of the flock was a legitimate way to distract oneself.

Although, of course, confession has always been a matter of confidence, the admission to religious, economic or sexual aberrance would have made the indigenous parishioner very vulnerable indeed.

As we do not have any documentation about the actual practice of confession, it has to remain open to speculation whether the parishioners, out of fear, would tell the priests what those wanted to hear, or whether they would have invented some minor ‘sins’.

The Quechua people did, indeed, have a concept of sin, but it reflected the individual’s or community’s negligence of the very important ties of reciprocity with the deities and the disastrous consequences this might have, rather than the classified system of personal sin through disobedience. This raises the question whether they would have seen both kinds of ‘sin’ as comparable and whether they would have put much weight on the Christian practice.

From the point of view of the priest, the confession gave him, in case he wanted to use it, a powerful tool of social control to play his indigenous parishioners off against each other.

Further Reading:

Barnes 1982 Catechisms and Confessionarios; Dedenbach-Salazar Sáenz & Meyer 2005 Die “Ayuda a bien morir”.)

Publication in Indiana:

Publicación de las contribuciones sobre confesionarios en:

Indiana, Instituto Iberoamericano, Berlín [open-access]

https://journals.iai.spk-berlin.de/index.php/indiana/index

[21.12.2018]

Vol. 35, Núm. 2 (2018)

Tabla de contenidos

Dossier:

Idolatría y sexualidad: Métodos y contextos de la transmisión y traducción de conceptos cristianos en los confesionarios ibéricos y coloniales de los siglos XVI-XVIII

| ‘No fornicar’: el discurso de culpa, penitencia y perdón en el Confessonario en lengua cumanagota (1723) de Diego de Tapia

Roxana Sarion |

PDF

55-87 |

| O primeiro mandamento da lei de Deus em confessionários tupi jesuíticos dos séculos XVI e XVII

Ruth Monserrat, Cândida Barros |

PDF

89-117 |

| De ‘Dios’, ‘pecados’, ‘demonios’ y otros vocablos en dos confesionarios en lengua náhuatl del siglo XVII

Rosa H. Yáñez Rosales |

PDF

119-149 |

| El pecado en la lengua tarasca (purépecha): Conceptos para la confesión en el sexto mandamiento del confesionario de fray Ángel Serra (1697)

Cristina Monzón |

PDF

151-173 |

| “¿Sueles decir al hechicero: ‘Adivina para mí’?” – Funcionalidad gramatical en las traducciones al quechua de cinco confesionarios coloniales

Sabine Dedenbach-Salazar Sáenz |

175-207 |

INDIANA

ISSN (print): 0341-8642

ISSN (online): 2365-2225